The author’s odd, old and strong grip is very stiff against recoil —and very tiring. There are better ways.

We old-time shooters have a lot of bad habits. Many of us are inveterate trigger-slappers, while others can’t keep our support-hand index finger off the triggerguard. Me? I have a death grip on handguns. In the early days, we tried to control recoil and sought to dominate it, eliminate it and minimize it. It took a long time to discover that recoil didn’t matter, at least not when shooting fast and accurately. The real secret was developing a proper stance and technique that allowed faster target acquisition than muscling the handgun into submission.

While blazing the trail, we also experimented with handgun holds. Ask a slew of instructors, and they’ll tell you everything that works. They just won’t agree on what works. Some will instruct even amounts of pressure with each hand. Others advise even but light pressure, or was it, “Try to squeeze the oil out of the grips!” Some will say a 60/40 split of force and others a 40/60.

Right handers will be told to crush the frame with your left hand and let the right hand do nothing but position the trigger finger. This is to make sure the hand is relaxed and that you aren’t squeezing with the whole hand when pressing the trigger. Or clamp the frame evenly between your hands, using side-to-side force and not front-to-back force, to balance forces.

Arms play into this, also. Arms bent, arms straight, one more than the other — we’ve experimented, tested and competed with all of them. We talked about that part of the equation and the history of stances some columns ago. I’m less fixed in my ways on stance than I used to be. I’m with Bruce Lee on that one, if I may paraphrase: “In the beginning, I didn’t know stances and just shot. Then stances became everything, and I worked hard to develop a stance. Now, I don’t think about stances and just shoot.”

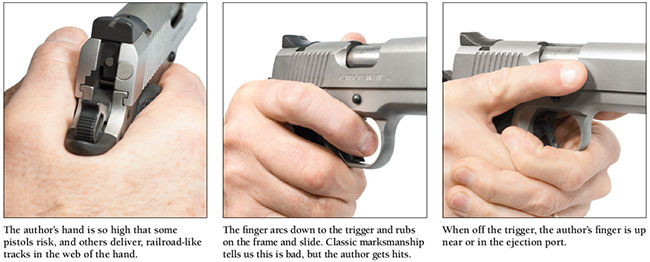

But the grip? I’m OCD about that. My grip is a peculiar combination of various tricks and bad habits learned through the decades. To start, I grip very high with my firing hand. With revolvers, I’ve had the hammer spur contact the web of my hand as it comes back in the double-action (DA) trigger press. On pistols, the tang is the only thing that keeps the slide rails from churning twin tracks down the top of my hand. On some pistols, I’ve gotten those tracks anyway. In fact, my hand is placed so high on 1911s and some other pistols that I find many ambidextrous safeties are hard or impossible to use. The knuckle of my right hand also rides so high on the frame that the paddle on that side can’t clear it.

My grip is such that my trigger finger comes down to the trigger and rubs the slide and frame as it arcs down into the triggerguard. If I lift my trigger finger straight out of the triggerguard, it points up at the ejection port.

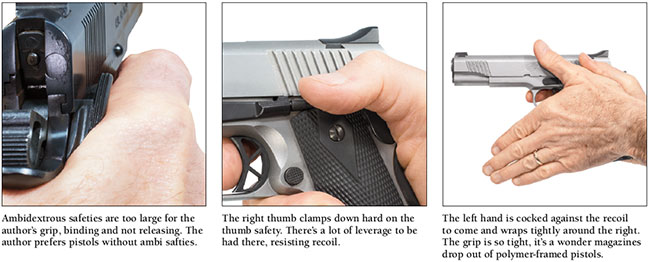

On the other side, my thumb rides the safety. Yes, I have broken at least one thumb safety from the excessive pressure applied and recoil leveraging against it.

Meanwhile, my left hand is working overtime. To give you an idea, point your left hand out in front of you, palm to the right. Point your thumb at the ceiling, and your fingers at the floor. You have to bend your wrist to do that. This is the position of my left hand on the frame, essentially clam-shelling over my right hand’s fingers. When on the gun, both thumbs point at the target. The wrist of my left hand is locked, and heel of my left hand is wedged tight into the checkering or other nonslip pattern of the grip surface or frame.

But there’s one detail that remains: my left index finger. It is wrapped around the fingers of my right and goes into the gap between the right trigger finger and its brother, the second finger. It rides on top of the second finger in a position known in the old days as the Ayoob Wedge. The left-hand index finger provides greater resistance to muzzle rise. How much? After a day of shooting, my left-hand index finger is more sore from handling recoil than the right-hand one is from pressing the trigger.

After spending untold hours of range time practicing on pins, I found that my response to USPSA/IPSC was to get my hands into that position as quickly as possible on the draw.

The last art of the jigsaw puzzle is grip. I squeeze the frame for all I’m worth. Were I trying any harder, I would not be surprised to see drop-free Glock mags — and they hate that term — fail to drop free.

The results are an altered zero. I have learned that I cannot depend on someone else to sight-in handguns for me. A longtime friend of mine, a nationally known pistolsmith, sends handguns back with the sights machined to his zero, knowing that they will hit low for me. I range-test, provide the offset, and he does the final machining on the front sight in a few minutes. People who have watched me on Guns & Ammo TV comment on the decreased muzzle rise of pistols I shoot and ask if I shoot downloaded ammunition to look good. Usually with a sly grin, I respond in the contrary, “Nope, we use factory-new, full-power ammo supplied for the show.” I’m not sure if it is the thought of the muzzle rise or the cost of the ammo shot for the cameras that they are more surprised by.

The left index finger, in the Ayoob Wedge, does its part to resist recoil. And pays in soreness after a long practice session.

I developed my grip style back when I was shooting in a PPC league at the local sheriff’s office. I built target-soft .38 Super (everyone else shot a revolver then), and I could get it to run for three entries each night, 180 rounds, without a problem. None of the deputies could go through a single magazine without a malfunction, even when it was clean. My grip was so hard that the pistol might as well have been in a vise, and their grips were not as tuned.

So, is this a grip you should emulate? Probably not. Your hands are not my hands. I have large, slender hands, and while it is sometimes hard to find gloves that fit, I am by no means the guy on the range with the biggest mitts. I’ve just tortured mine into such a particular grip that it’s even difficult to get SIG Sauer classic P-series pistols to lock open when empty. My thumb rides right in line with the slide stop lever.

All this can be work. A day’s practice leaves me with sore hands. Younger shooters who let the recoil ride and time themselves back to the target aren’t working nearly as hard, and probably won’t have the hand, wrist, elbow and shoulder problems that we old-timers suffer.

So, the question remains: How hard should you grasp your blaster? I’d suggest, hard enough that you won’t drop it. Hard enough that if someone tries to snatch it away, it won’t come free easily. Beyond that, you’ll have to blaze your own path with a little trial and error. Experiment on your regular range trips, use a shot timer and find what works. If you’re serious, keep a training log and jot notes. Hard work always pays off, though not always the way you might have expected.